The Woman with Mice

The Woman with Mice

This is the truth. The mice were really her whole problem.

When they had taken over the woman’s house, and they had chewed up her insulation, and munched her wires, and one of them had had the nerve to waltz out from under her fridge, and then, just sit right there and stare at her, she had said to her herself, these monsters must go. This is what she had said, because the problem had gone beyond discussion.

Then, George, at Chagrin Falls Hardware, had sold her 30 JAWZ mouse traps.

These heavy-duty, fully plastic mouse traps advertised a new and expanded catch area and a bait reservoir that had sensitive triggers. Over the phone George had said, these babies will all but guarantee you have no misfires and plenty of dead mice. He had assured her that these special JAWZ traps had biting teeth to prevent rodents from escaping.

That’s all you could really ask for, she had thought, to know reliably that when your time to go had come, that you would indeed go, and not linger for stupid things, like equipment failure.

When the woman had driven down the hill to the hardware store, George had gotten the mouse traps all packaged up and ready for her, so she didn’t have to go inside the store to get them. Since her failed cardiac ablation procedure, and since Covid had come, she didn’t go inside stores.

The woman is pleased with her efficiency. The last six days she’s emptied 23 traps. A work like this is never done though, which is what the woman says when people call and ask, how goes it with the mice?

She props her cane at the bottom of the stairs leading to the widow’s peak and adjusts the blue plastic grocery bag of dead mice. As she climbs the stairs, she gags a little from the smell. The woman has double bagged, but death is persistent.

Here, at the top of the house, the mice have left evidence of themselves spread about, as if to say, look how I can get into all of your places, look how I can haul string from your basement and snotty tissues from your bathrooms and fluff from who knows where, to build a nest in this drawer that you forgot about, all the way the hell up here.

In her basement, eliminating the mice from everything they had touched had been impossible. They had eaten through the flimsy rice bin and the chocolate bar wrappers. They had wrecked the stash of tea. They had feasted on granola bars, pasta, and wheat berries. The woman had to toss everything out and the whole room had to be sanitized.

Monsters.

She had thought that if she could confuse the mice by taking their stuff, they would be lost, and then perhaps they would leave. Instead, they had eaten her leftover calcium channel blockers from the little plastic bag in the closet across from the shower in the master bathroom. They had eaten a small number of Propranolol as well, but had left untouched the alpha-adrenergic agonists, the corticosteroids, the 500 dollar a month Ivabradine, and the anti-arrhythmic. Two mice had dropped dead near the shower. She had been filled with sadness and she had wished they had at least considered going away.

Monsters.

Several hundred dollars after visiting her Toyota dealer, her minivan continues to make a smelly, clicking noise when the air is on. That smelly sound might go away, might not, so, let us know, the Toyota dealership mechanic had said. The mice had nested in the air box of the woman’s minivan, which had left her wondering what the mice would think when they discovered that she had emptied their warm and full places. Some things you had to make leave.

Monsters.

They had moved into the space behind the dumbwaiter. This had been their headquarters. Centrally located. Easily defensible. Not a place the woman would have thought to look first. It was the exterminator who had found that nest. You got herself a problem here, if you don’t mind my saying so…if I lived here, I’d start fightin’ back. Walking silently, while everyone had slept, the woman had taken their mice things, their home things.

Monsters.

Once, when the woman had been sleeping in her octagonal room after her husband had started snoring for the night, she had heard a stirring. A family of mice might not think that entering into the woman’s room of eight would have been a definite source of morbidity for them. This is to say, that the family of mice and all of their friends, who came to chew up her early 1900s chimney cabinet, with the shelves full of loved things and inside walls all scribbled with permanent marker, didn’t know of the certain death that this would cause them. The mice did not understand that the killing came from some exotic property of the women’s precious things kept in the chimney cabinet, and that the woman would never, ever talk about the act afterwards or write about it, because who even has the words for that?

Monsters.

And why is it, the woman wonders, why the hell is it that don’t we have the words to talk about monsters? She says pathological fatigue, and people suggest she get a dog. Which makes them feel much happier about themselves. She says she can’t stand without shaking. People suggest yoga. With such certainty. She says she can’t breathe or swallow and people say she should try sticking her face in ice water three times a day. She says adrenaline dumps at night and people say things like, have you tried meditation? Like it’s prescriptive. She can’t generate a voice. The woman is losing her fucking voice. So, she feels like this makes her something else entirely.

Monsters.

And the woman knows monsters. She learned monsters from Robert Carter who knew monsters first. In his human life, he was Robert Carter, owner of Family Music Center on North Shadeland Avenue in Indianapolis, Indiana. In his monster life, he was Sammy Terry, a play on the word cemetery, monster host of Nightmare Theater, which broadcasted from WTTV each Friday night in the 1970s.

Every Friday, when the woman was young, she’d beg her Nana to let her stay up late and watch Sammy Terry.

Don’t let her watch, Alice, her Papa would quietly warn her Nana. All of his warnings came quietly. She’ll keep us awake all night saying there are monsters.

But her Nana always let her watch. This is a thing the woman and her Nana agreed upon without ever talking about it.

The woman had needed, even then, to be reminded of the gasp constantly caught between her lips. She had wanted to understand the things that talked in the night. She had needed to sit straight up in her bed, and then lay back down again, certain that there was nothing swaying about in the house, that she was only coursing with her own blood, that she was just the sound of distant traffic up by the new McDonalds drive-thru on the corner of Bridge and Gilbert, that she was not the sound of someone uninvited.

After Sammy Terry had ended, after her teeth were brushed, and after the woman’s Papa had turned out the lights in the whole house, and her Nana had tucked her in and their voices from their bedroom were barely a buzzy mumble in the restful night, the woman would lock eyes with the mirror over the dresser at the end of the bed and whisper, there are monsters.

Once when she was not grown and not old, the woman wrote, in lives, monsters are one of the leading causes of people scattering themselves about. This is how people end up buying shelves of ketchup and saving drawers of take-out forks that they don’t need and that they’ll never, ever be able to use. If they aren’t scattered across seven counties from that, then, they’ll be coaxed into only eating cheese and microwaved hot dogs and giving away their hard-earned money to buy their salvation. They’ll close themselves off like old rooms too mean to use, and then soon after, they’ll be dead from scattering. She wrote that because she had seen it.

The woman would lie awake in the dark long after her Nana and Papa were asleep, waiting for monsters and thinking of how she would get rid of something like that, something that wouldn’t go away. She always did that until sleep came.

If the woman were being honest with herself, and if anyone were asking, she would say that she has always known that monsters cannot leave on their own, because they have a habit of falling dead, and then waking up embedded in extremely fragile places, like in a colon or in the greater trochanter tendon and gluteus medias muscle or in the sinus node of the upper right chamber of the heart or in vocal cords or in bladders, and then, of course, in relationships, where they’re the heaviest with resentment and elimination. They stagger with stealth, through immune systems. They ooze down nerve pathways, their fingertips brushing worn synapses, voices echoing off pieces of their DNA, trails of themselves left in the brain, in the heart maybe, or in the blood, no one is certain, but they keep the light off and they stare into the dimness of everything left undone, while they drag their claws across functionality, obliterating it, and then dissolving into pain and regret.

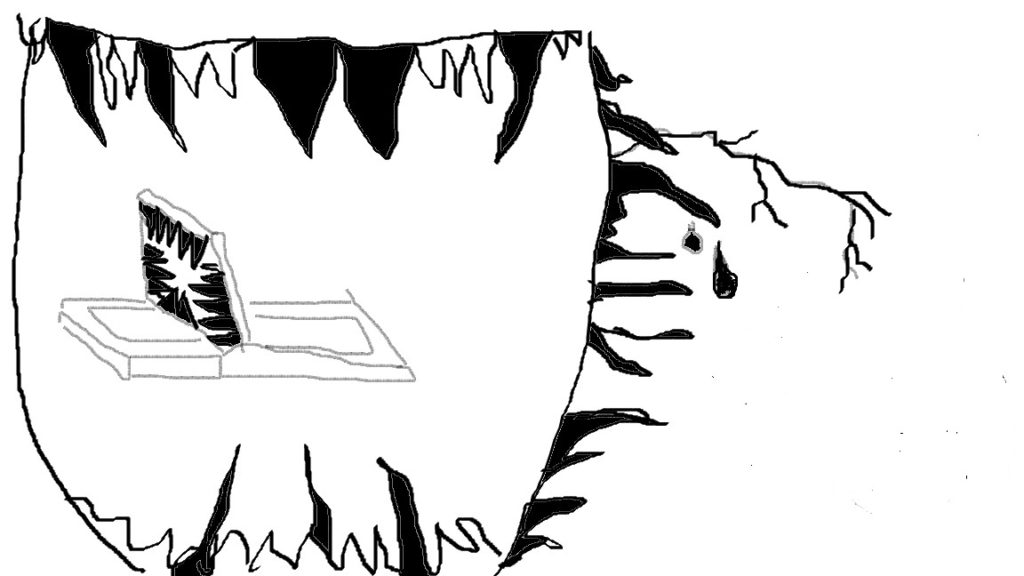

One day the woman’s youngest son painted a haunted house so huge that it filled an entire two-foot by three-foot page. He then added a tremendous, fat, brown lightning bolt, jutting from a window at the heart of the house. The lightning bolt shot straight up to the right, at a diagonal, and off the page. Hearts of haunted houses are filled with monsters and my lightning bolt is how the monsters get out, he had said.

He was right, the woman thinks. To get rid of something that won’t go away, to get rid of a monster, you have to remove its heart, except, in her experience, you have to do that by hand. It’s a nasty business, but it’s just a matter of gathering yourself to do it.

The woman counts the stairs on the way down out of the widow’s peak.

One. Place both hands on its neck.

Two. Position thumbs at base of neck.

Three. Apply pressure and hold.

Four. Drive knee into its groin.

Five. It’ll be stupid with blood and howls, but nail its cloaked body to the floor anyway.

Six. Take its pale face in your hands, its blood into your mouth, and put your daggered eyes to its skin.

Seven. Electrocautery to tissue.

Eight. Saw to middle sternum. Incise pericardium. Then the aorta.

Nine. Do not cannulate.

Ten. Steal its rhythm and replace it with nothing. Everything is wrong there.

Eleven. Plug the hole that you’ve made with your huge and steady grief, and then suture inside of it everything that’s passed from your tongue to your brittle brain and from your brittle brain to your heart.

Twelve. Lower your head and wail quietly behind your eyelids.

It’s always harder work than she remembers. The woman reminds herself of this.

When a monster heart beats in a chest with a huge and steady grief, when it shelters in the spaces between insensibility and the last dose of beta blocker, when it tastes like the no end in sight void, you have to remove it. The woman more than knows this. She feels this.

Downstairs, on the way to the garbage cans by the shed, just as she steps from the garage onto the driveway, out of the corner of her right eye, the woman catches a teeny flicker of black moving on the driveway where nothing should be moving.

A mouse is dragging a JAWZ trap across the driveway. She hears its very faint call. Its leg, the woman thinks, is caught in the trap with the biting teeth designed to prevent rodents from escaping.

She thinks, this is evidence right here on my driveway, of what happens when you cut a thing off from everything it knew, but you fail to end it.

After this, it is difficult to separate what happens from what seems to happen, because she thinks that anything she does to help the mouse, will surely help the mice get their grasp back on her house. The woman tells herself this out loud. She tells herself this out loud several times over. She had hoped the mice would mention something about leaving, but instead they had mobilized, and now this one’s aliveness is making her tremble. This one is refusing to leave a world that clearly keeps trying to cut it into smaller pieces.

The woman thinks that she cannot say what’s actually happening, she cannot possibly say what’s happening, because she refuses the out loud words for this, for this thing she had sought a guarantee against, but maybe, maybe, she could write the words. Maybe. Someday. Someday, if she ever did write about this, if she ever did speak the truth about this, the woman would say that she had lain awake for 19, 457 nights, a fearful creature prone to fearful decisions, a gasp caught on her lips, because of things that won’t go away. She’d write that she had known a secret, that she had known how to surgically remove the hearts of monsters and then wail quietly behind her eyelids. She’d write that a work like this is never done. And that it’s always harder than she remembers.

For now, though, on this chilly autumn afternoon, she knows what this is. This is just equipment failure. That’s what this is.

The woman tells herself that a mouse doesn’t just drag a mouse trap across her driveway, its bloody, broken leg caught forever. That doesn’t happen. She tells herself that this is something else entirely. Monsters. The woman tells herself, this is monsters.

Imagine not believing in monsters, she thinks to herself, and then she limps inside to reset the traps.

I see and feel every bit of your writing. Many gifts have been taken from you, but not this one