What It Means to Make Groundhogs Explode

What It Means to Make Groundhogs Explode

What It Means to Make Groundhogs Explode

Exploding Varmints, Vol. 1 is a twenty-six minute long video of two men shooting groundhogs with explosive ammunition. Tinny synth music plays over shot after shot, varmint after varmint, each being ripped to shreds by a threat they could never conceive of.

The intro claims it’s educational, and that the tape can be (and ought to be, is the implication) shared with friends, family, and clergy. It ends with what I can only call the Nicene Creed of varmint-hunters:

“What’d you say? Let’s go explode some varmints!”

#

Before I start, I’m going to go over a list of deaths that I feel like a varmint would consider possible.

- Torn apart by a hawk, eagle, or other bird of prey

- Eaten by a coyote or wolf

- Mountain lions certainly exist in varmint cosmology

- Automobile(?)

The particularly perceptive among you will note that exploding doesn’t appear to be on the list. This is because in no conceivable universe does a groundhog think it could explode. If you doubt me, just remember that I’ve seen Exploding Varmints, making me more or less an expert on varmint psychology.

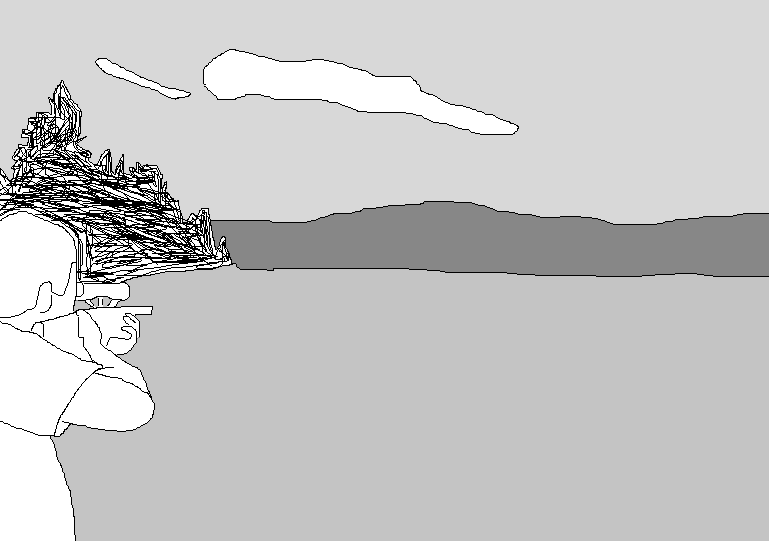

Here’s an example: the protagonist (referred to as ‘Mr. Hunter’ on the distributor’s website, introducing himself as ‘Lewis’ in the video itself) takes a shot and misses. The sand explodes a few inches from a confused groundhog. He racks the bolt of his rifle and takes another shot, missing again, while the groundhog, the archetypal varmint, he-who-is-to-be-exploded, just stands there, dumbfounded.

It could be afraid. It could know that something is happening, just not what. And then it dies.

Personally, I prefer to think that it’s confused. It’s less depressing and, more importantly, more meaningful.

Mr. Hunter is an angel of death, sent by an unseen rancher to clear his land of all that could be called ‘varmint.’ His rifle is Indra’s arrow. His tone is playful and mocking. Apparently, he alternates shooting with another person, which raises the question: who is Mr. Hunter?

Is he Lewis, the shirtless man whose joy upon decimating yet another varmint can only be described as unsettling?

Is he the unseen cameraman-alternate?

Are we Mr. Hunter?

Or are we the varmint: helpless, confused. Exploding.

Cartwheeling through the air, torn in half by something we have no possibility of understanding, our entrails flapping through the air.

And Mr. Hunter laughs. “I love doing this, man!” he says, smiling. “This is excellent!”

#

#

I’ve got family who like to hunt, so once the initial shock wore off, the video seemed less obscene and more blunt. After the initial montage ends, Mr. Hunter reappears to explain why he brought an apocalypse to Northern California.

Varmints are a pest. This is not something you can debate. They destroy crops, they damage property, and their holes can injure cattle. In other words, they need to be culled every now and then.

More importantly, poison is illegal, not to mention crueler: despite the theatrics, death by explosion is comparatively merciful, not to mention good for the animals who can’t buy explosive ammunition… the hawks, the coyotes, the eagles.

“Nothing gets wasted up here,” he says, beaming. “For all you nature lovers not understanding what’s going on, it all goes back into the food chain.”

This is when my understanding of varmint cosmology began to take shape. Mr. Hunter is not Kalki. Slaughter is not the point; he kills so that other hunters can eat.

In short, Mr. Hunter has more in common with God than the Devil. What he does isn’t always pretty, and his methods are incomprehensible and terrifying to his subjects, but there is a purpose. A meaning.

Eerie, ethereal music plays against the screaming of gulls as the camera zooms in, an eighteen-wheeler gliding along the horizon against the pine-covered mountainside. A pair of bald eagles fight over his gift to them, screaming while he mutters indistinctly. The older of the two takes flight, gliding across the field in search of something else, something the same, something already dead.

It swoops down, hardly stopping, picking up a present from him, and takes off towards the mountains, pine and redwood blurring together in a VHS haze.

Nothing goes to waste.

#

There’s something else. It creeps up on you then hits you faster than a .22LR hollowpoint. This isn’t an educational video.

It’s a home movie.

The cameraman-alternate racks his rifle and says to Mr. Hunter, “watch this, son.” The footage takes a break from the at this point tired montages of exploding prairie dogs and pans left to show Lewis, gunshot still echoing, most of his body covered up by a black circle, showering underneath an irrigation system. He comments on all the bucks they’re seeing today and then right after he pulls the trigger, carcass still somersaulting in the air, laughing, says: “Oh, Dad, you like that?”

The footage starts referencing people (family members? friends? clergy?) they know. Bert. Beebee. Gary.

“Bert, here’s another one for you, buddy.”

“Ahaaha. You like that, Beebee?”

“Watch this one explode, Gary.”

Watch old episodes of America’s Funniest Home Videos and you’ll realize that this is the same thing; the only thing that’s changed is the target demographic. There’s something deeply unsettling to me about watching footage like this, filmed god knows how long ago. I think about the people inside the tape, doing the same things over and over again. Here, it’s still June 23rd, 1995.

And there’s always the why. Why was this made, why did you let Tom Bergeron see that, why would anyone record their family. It makes it worse when they’re gone.

I see relatives I’ve never met on Facebook, commenting on scans of old, yellowing family photos, ones where everyone is smiling and young. This was so-and-so’s communion, or this was Christmas, 1961. Old women wistfully contemplating the deaths of everyone they’ve ever loved, in public. Evidence of the most horrific truth that we’ve tried to suppress every day since we figured it out: one day, all we’re going to be is a memory.

And sometimes not even that.

This is all we are, when the lights go out. The memories we have of one another, hopping from person to person until we reach the end of the line. But it looks like, for now, we found a way to cheat death, whether it’s through tapes of exploding gophers, or old photos uploaded to the internet.

Our time here is as brief as our graves are deep. All we really want is to be remembered, and now we’ve found a way to live forever. It’s mankind’s greatest achievement (at least until we find a cure for cancer.)

#

The main hunter – using his real name feels weird because now I’m actually thinking about him as a person and not a funny character in a low-budget hunting tape from nearly three decades ago – doesn’t look that old. The other one sounds older, and his tone’s noticeably a lot more subdued.

“Tell ‘em where we are.”

“We’re in Montana, now, and… we got a little prairie dog here that’s gonna die real bad, real fast.”

It’s unnerving. Like the laugh track of a sitcom that stopped airing during the Kennedy administration: dead air. Immortality that no one asked for or even knew they were getting. Years from now, when he’s gone, he’ll still be there. Montana, 1995.