The Ultimate Self-Effacement

Here in Heaven the clouds are perfectly white, the sky is perfectly blue, and the light is unequivocally divine; the forms exist in an ethereal way suggestive of non-existence yet inexorably there, insisting that I perceive them. That “I” is less emphasized, less all-encompassing and autocratic than in its normal sense; the “selfness” of my self has been diminished, my presence more incidental, less consequential than it was before I found myself here, before I wrote my own obituary.

That idea, to write my own obituary, was inspired by the death of my Uncle Gavin, after I had read his obituary in the Cape Cod Gazette. I was home for Christmas at the time, a condition with its fair share of ramifications. It meant my mom’s cooking permeated the rooms and hallways of my childhood home, the aroma of the chicken divan or pulled pork as much a part of the holiday atmosphere as the garlands on the bannisters or the lighted tree in the den. It meant my mom would soon stick her head into my old bedroom to ask that I screw in the bulbs to the plastic candles in the windows, completing the house’s external appearance of Yuletide harmony. It also meant Alana was having us over that night to hang out in her basement, a time-bending experience, the six or seven of us lounging on couches, drinking lemonade, eating her mom’s cookies as we had done when we were in high school, so much the same as it had been- Kevin carrying the conversation, Maggie waxing nostalgic, Sean playing the court jester- and one aspect so indelibly changed, so radically different- their attitude toward me, with their desultory smiles when I enter the room, their earnest attempts to draw me into their mundane conversations, and the shared understanding that they only invited me because it would be weird one year suddenly not to.

Before I’d encountered the obituary, I was sitting at my desk, playing a little game with myself. The two curtains in the room were a velvety color somewhere between red and purple (a hue so different from what I see in the bloodless landscape around me now, where everything is blue or white and imbued with a pleasant coolness despite the intensity of the light, that it’s hard for me to imagine it). The game consisted of cutting off the circulation of blood to my index finger with a bit of fishing line, then watching the skin redden above the tiny tourniquet until it matched the color of the curtains. It’s fortunate the fabric wasn’t a tince darker, or I’d have had an amputated digit on my desk to contend with.

There was a rope under the bed, placed by my father to provide escape in case of fire. I considered wrapping it around my neck to play this same game with my head, but my room lacked the requisite mirror for self-observation.

My mom’s thumping footsteps distracted me from my game as she ascended the staircase.

“Hey Billy, can you screw in the lightbulbs?” She continued on into her bedroom before I could acknowledge her.

I got up and pulled the fishing line from my hand. There was a touching fragility to the bulbs, so vulnerable between my thumb and throbbing forefinger, and I wondered how hard I would have to squeeze for them to shatter.

“You know, Billy,” my mom said, in that raised-but-still-pleasant voice she uses for addressing people in a different room, “Uncle Gavin’s obituary is in the paper today.”

“Oh yeah?”

“Here it is if you want to read it.”

I heard the faint rustling of the newspaper as it landed on the bed behind me, then my mom thumping back down the stairs.

I won’t rehash the words that appeared beneath my uncle’s name, since I’m sure you can imagine them already. There were four other obituaries on the page, all more or less the same. So and so died surrounded by their loving family. They graduated from this or that high school or university before embarking on distinguished careers in whatever profession. They were all greatly loved for their many endearing qualities, and to commemorate their lives donations can be made to some or other charitable organization in lieu of the flowers you’re assumed to be on the verge of running out to buy. It’s like the families of the deceased all download the same obituary template.

Why did I find this standardization so revolting? Is it because a human life is so special, so unique, such a magical settling of the colored sand in the once-shaken cosmological kaleidoscope that to see it distilled into formulaic inanities is repulsive? Or is it because that uniqueness, that specialness, that magic is a mirage, a fabrication that’s painfully revealed in those banal eulogies that depict human lives as the trite, inconsequential, meaningless substantiations of consciousness that they are? I think it was in a rebellious posture against the latter possibility that I decided to write my own obituary.

Across the hall in her own bedroom my sister was cleaning her birdcage, while outside my father shot empty cans full of BBs, staying sharp for the spring’s onslaught of squirrels among his birdfeeders. For a moment the clattering of cutlery downstairs, the rattle of birdseed, and the clinking of the BBs cluttered my mind with such a cacophony of sound that I couldn’t concentrate, but, with a mental thrust of determination and confidence in the value of the task at hand, I leaned over my notepad and got to work.

There would be no banal cookie-cutter statements for me. My obituary was to be insightful, telling, even literary. To maintain a satirical adherence to the classic obituary form, I decided to start with the death scene. I pressed lightly down with my pencil, in case I needed to erase.

William “Billy” Davidson died at Cape Cod Hospital on March 27 at 8:38 AM, with his parents and his sister at his side. His father, at 8:37, had begun to dig with a toothpick at a piece of chicken wedged between two molars. His mother, at 8:33, had started reading an article about Kim Kardashian’s political activism in People magazine. His sister, at 8:29, had begun watching Snapchat stories showing her friends at a party the night before. All three tasks were completed, his father removing the chicken at 8:39, his mother finishing the article between the nurses’ condolences at 8:46, and his sister watching the last of the herky-jerky videos at 10:22 on the car ride home from the hospital.

Now as I look back at that moment from here among the clouds, I have to admit the characteristic self-pity is a bit over the top. But at the time, sitting beneath the lustreless glow-in-the-dark constellations of my childhood bedroom, this imagined apathy from my family felt strangely empowering, like it justified a vengeful attitude of my own. I reread my work and, feeling pleased, added an artful telling of my biography.

Billy was born on August 12, 1992. He spent three semesters at Lehigh University, a year at Umass Boston, and a semester at Franklin Pierce, before embarking on a jumbled mixture of restaurant, construction, and landscaping work, interspersed with failed applications to tech companies that claimed not to require a bachelor’s degree. He most recently worked as an “assistant chimney sweep”- not a chimney sweep, mind you- he never swept a single flue, but an assistant, carrying inside the vacuums that caught the errant dust particles flushed out by the brushes. Before his death, his position at the company was imperiled by the fear of heights that made him useless in the installation of chimney caps and flue liners, although he did sometimes make the other workers laugh. Billy will be buried on April 1st in his family’s backyard, alongside the recently-deceased cocker spaniel. In lieu of flowers, try to be thankful, next time you’re sitting by a cozy fire, not just for the chimney sweep whose brush has eliminated the risk of a sudden combustion, but also for the assistant chimney sweep, dutifully lugging vacuums into countless bookshelf-lined living rooms, who by all means could be a kid happy for the job or a genuine apprentice on the path to a career as a bonafide chimney sweep, but who might also be a twenty-seven year old college dropout with three years worth of student debt but no degree, no ticket into the keyboard thumping, urban-dwelling, someday-will-pay-off-the-debt-before-spending-their-way-into-more young professional class, and lacking also the natural grit, punctilious work ethic, and practical know-how for ascension in the blue collar professions, watching the world rise without him like a swamped dinghy whose mooring is too short for the rising tide.

That I had a pessimistic take on my life wasn’t surprising, but I was a bit taken aback by the extent of my evident despair. I knew I wasn’t happy, but I never would have admitted a dissatisfaction as profound as that which I revealed in my writing. And yet, I could only assume it was this attitude, exposed without scruples on a paper no one would ever see, that more closely reflected my true disposition than the affected personality borne not of my soul but of the constant interactions in the social space between myself and others.

As much as I didn’t want to, I knew I would go to Alanna’s. But I was nauseated by the thought of leaving this obituary tucked away in a drawer while I attempted to feign normalcy with my old friends. The discrepancy between the truth revealed on the page and the version of myself I would present in Alana’s basement was so great that I would feel it tearing me in two. Somehow I had to bring them closer together, and, given the choice between adjusting the social “me”- disturbingly morose and worryingly off-kilter but still capable of surviving in human society- or altering the written account on the paper, it seemed obvious what I should do. And so I erased the biography.

In its place, I decided to describe the life I’d liked to have lived. That’s a version of myself I felt better about leaving in a desk-drawer. In a way, this imaginary biography would actually be truer, since a person’s ambitions reveal so much more than their failures anyway.

Billy was born on August 12, 1992. He abandoned his studies at the age of twenty, having developed the “BuddyTime” application that he later sold to Google LLC for $127 million. Much more than a mere entrepreneur or tech pioneer, he was widely regarded as a “spokesperson for the millenials,” giving voice to the myriad concerns and telescopic ambitions of America’s most strident generation. He wrote multiple self-help bestsellers and appeared regularly on CNN, MSNBC, NPR, and several popular podcasts. His millions of social media followers will doubtlessly miss his wit and wisdom, as well as his uncanny ability to lead from beyond the screen. There will be a public celebration of his life at the Barnstable County Fairgrounds. In lieu of flowers, please consider a donation to the Bill Davidson foundation, which will continue its contributions to groundbreaking artificial intelligence research in accordance with the vision of its founder.

I reread this virtual life, and felt pleasure coursing through me like I’d been injected with a narcotic. I read it again and again, but each time the euphoric effect was diminished. After my seventh and final reading, I felt only a dead weight in my chest and a cold tingling in my extremities. The words on the page represented a fantasy, a squelched dream, a painful lament. My real life was the one in the eraser shavings all over my desk, wiped to the side but still making a mess- a mess that couldn’t be fixed.

For the first time since I’d started writing, the sounds around me regained their dominance in my mental space. The clinking, the coo-cooing, the clattering all seemed too present, too real, too representative of the entirety of existence. I looked around the room, at the travel soccer trophies and the bookcase with Dan Brown and Johnny Tremain, and all the lines went blurry, like I was focusing on them too intently. The melancholic totality of it all made the cords binding reality tremble as if soon to snap, and the questions “what the hell is all of this?” and “how am I alive?” and “what does alive even mean?” asked themselves simultaneously in those porous borderlands where the conscious and unconscious mingle.

My agitation was such that I couldn’t quite account for my own actions. Even now, looking back from my current state of tranquility, I can’t ascribe to my behavior any continuous series of causes and effects. I only know that I erased the death scene of my obituary, clever as it was, and replaced it with something more biting, more carnal, more real.

William “Billy” Davidson died on December 23, 2019 in his childhood bedroom. His father was shooting cans with BBs in the yard, his sister was cleaning her birdcage, and his mother was preparing pulled pork in the kitchen. Ever assiduous, he had turned on both electric candles in his bedroom windows before his demise.

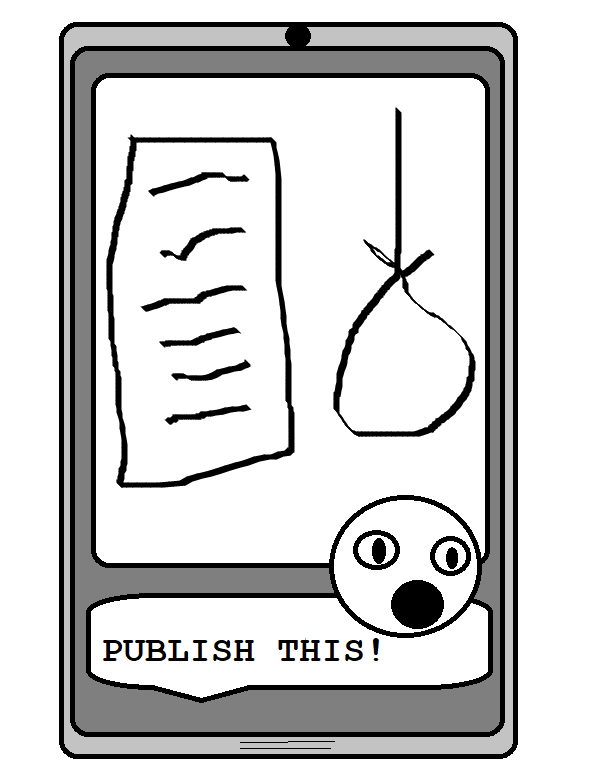

I scrawled “Publish This!” in the blank space at the top of the page and dropped down to my hands and knees to retrieve the rope from under my bed. (While down there, I remember now, I grabbed a long-lost sweater to wear to Alana’s, an interesting deviation from what was otherwise an unshakable single-mindedness.) Doubling the end of the rope, I tried to gauge what would be the proper-sized loop for my head. Would this do it? No, bigger. And how to tie it? Like this? Like this? In a sudden moment of clarity, I acknowledged it only had to look like a capable knot, and so I left it as it was and set it beside the obituary on my desk.

I took my phone out and made sure to hold it steady, not wanting the picture to come out blurry. My plan- hardly worthy of the name since it was devising itself in real time- would only work if people could read the obituary when they zoomed in. I included the eraser shavings in the shot, sure of their symbolic significance.

Once I’d taken the picture, I gave it only a brief glance before posting it on Instagram. Prompted to compose a caption, I typed out: “A little joke with myself! Hahaha!”

My humble piece of art appeared above the dogs, snowmen, and other such banalities stacked one atop the other in the application’s homepage.

My friends weren’t amused.

A lot’s changed since then, even though it’s only been a few days. That little stunt has exploded outward in my consciousness, altering simultaneously everything within and without, imbuing it all with that disembodied formlessness so well represented by the clouds, the vacant space, the ubiquitous light outside the window. Is life special? I don’t know. All I know is that I no longer take it seriously. You say that’s tragic. I say it’s liberating.

You didn’t read the introduction and assume I was dead, did you? No, no, the heaven I’ve described is about 30,000 feet above Albany. I’m on the plane back to Buffalo, where I’ll return to work tomorrow (if I decide to go). I’m sorry for the confusion. It seems I’m up to my old tricks again.