The CIA: A Model for Post-Individual Literature

The CIA: A Model for Post-Individual Literature

The CIA: A Model for Post-Individual Literature

In the CIA (Central Intelligence Agency), the individual is anonymous. The work they do stays hidden. If it’s noticed, it isn’t credited to any single employee, but to the agency as a whole. The CIA doesn’t create products or profits. It’s a collective that works together for the greater good, enriching none of the individuals who make up its component parts.

Through the Iowa Writers Workshop, the CIA took over American fiction. But instead of remaking literature in its own collectivist image, it seeded an anti-Soviet form of writing in which all stories are told through the perspective of the individual, a literature that cordons off any kind of knowledge other than what can be experienced through a character’s psychology. Everything else – science, society, faith – is only allowed in second-hand, after being processed by psychological realism’s strict point of view.

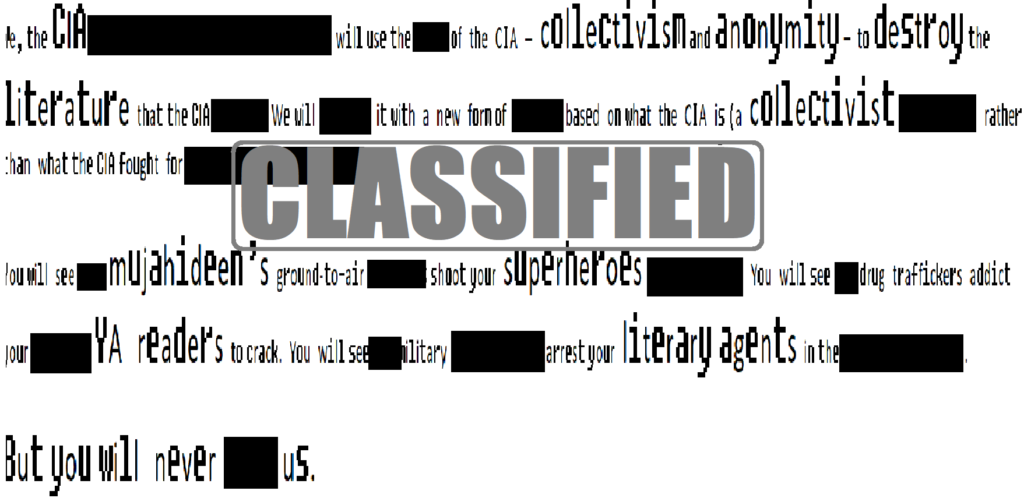

We, the CIA (Collective Intelligence Anonymous), will use the tools of the CIA – collectivism and anonymity – to destroy the literature that the CIA created. We will replace it with a new form of writing based on what the CIA is (a collectivist brotherhood) rather than what the CIA fought for (anti-Soviet individualism).

You will see our mujahideen’s ground-to-air missiles shoot your blockbuster superheroes out of the sky. You will see our drug traffickers addict your youngest YA readers to crack. You will see our military dictatorships arrest your literary agents in the middle of the night.

But you will never see us.

…

For years, we’ve avoided announcing ourselves to the world. But our plans have been discovered by corporate spies who passed them from to CEOs to lobbyists to prime ministers. Management consultants and special project teams have already marshaled a counterinsurgency, using our own strategies to fight us.

Our enemies adopted their tactics to fit the contemporary battlefield. In a world of young adult hooliganism, ceaseless entertainment becomes background noise. Today’s music is synonymous with traffic’s hum and wind’s rustle. It’s not something to be concentrated on but a mood, a setting, a constant unnoticed presence. Our enemies picked this artistic evolution as the ground where they would stage their attack. They birthed their own post–individual artists, using our strategy of anonymity in service of multinational corporations.

Their weapons are the non-existent musicians whose catalogues were recorded by AIs fed on thousands of hours of lofi study beats and chillout house. They’re hidden on streaming services, where, the moment listeners shuffle onto their songs, they explode like landmines.

Corporate-created robotic collectives wear sacrificial stock photo masks. They destroy post-individual art by stuffing it into an effigy-playlist and burying it in the background.

That’s why we had no choice but to reveal our name. We aren’t a collective hiding behind a fake individual. We’re boldly collective. Our work isn’t background noise, to be listened to on audiobooks as readers do their taxes. When audiences hold our work in their hands, they concentrate on it fully. When they put it down, it permeates their unconscious, becoming the glitch in their boardroom slideshows, the muscle twitch slamming brakes on their commutes, the self-conscious ego interrupting their manifestation meditations.

Jorge Mario Bergoglio is the first pope to liquify blood since 1848. The age of miracles is returning.

…

I once stood in a suburban grocery store’s cleaning products aisle, confused by the bright colors, trying to find detergent. As I read each brand name, searching for what I knew was there, a man walked toward me. His hair was wild and his shirt was stained. Because I instinctively avoided eye contact, I only saw the knife he held when he was two steps away.

He stopped behind my back. I pretended not to notice, pretended to continue looking for detergent. I couldn’t read brand names. I couldn’t see colors. I could only feel his quiet breath.

When I walked out of the store unhurt, I threw the detergent into my passenger seat. Through the windshield of the parked car facing mine, I saw an empty child’s car seat and a woman holding a half-empty half-pint of whiskey. She raised her chin, closed her eyes, and quickly drank what was left. Finished, she grabbed her reusable bags and went to buy groceries.

“Art is dangerous.” Artists repeat this mantra to protect themselves from critics who find moral fault with their work. The moralists are closer to the truth. Art isn’t dangerous – it’s disliked. Audiences intuit that art loves itself more than it will ever love them. If art hopes for a better world, it’s only because it believes a better world will be, by definition, a world in which it’s more adored.

Buried beneath anonymity and the collective, the individuals who make up this literary project commit to writing stories that are what art is – not dangerous, not hated, not controversial. Just disliked.