It Don’t Do to Presume

It Don’t Do to Presume

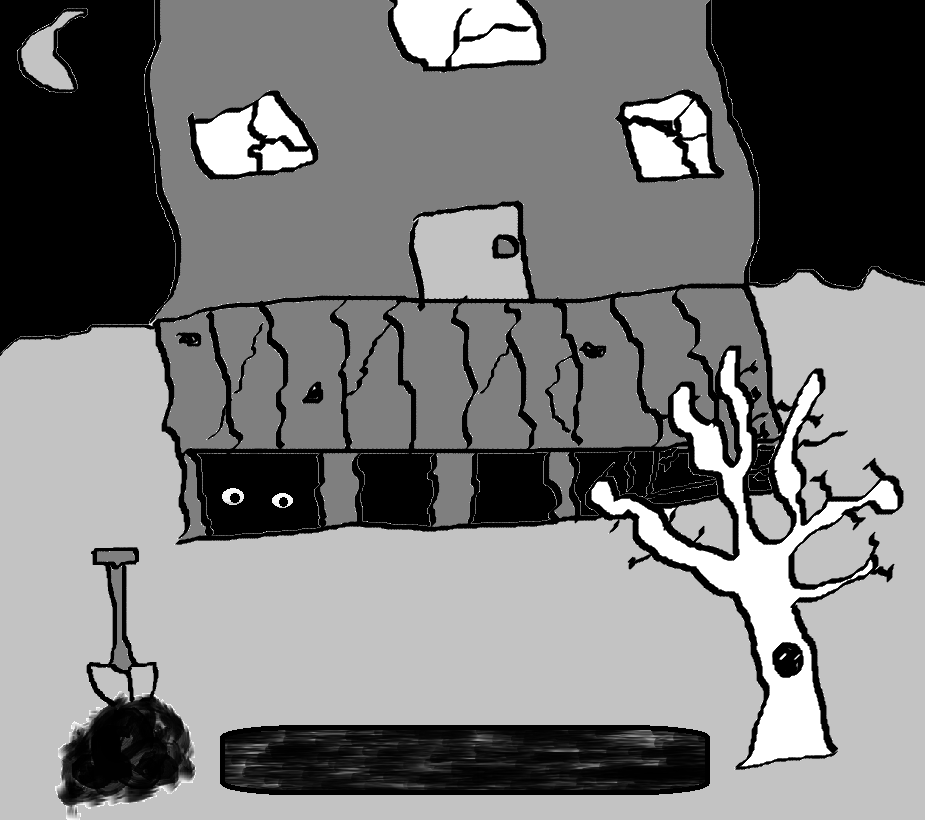

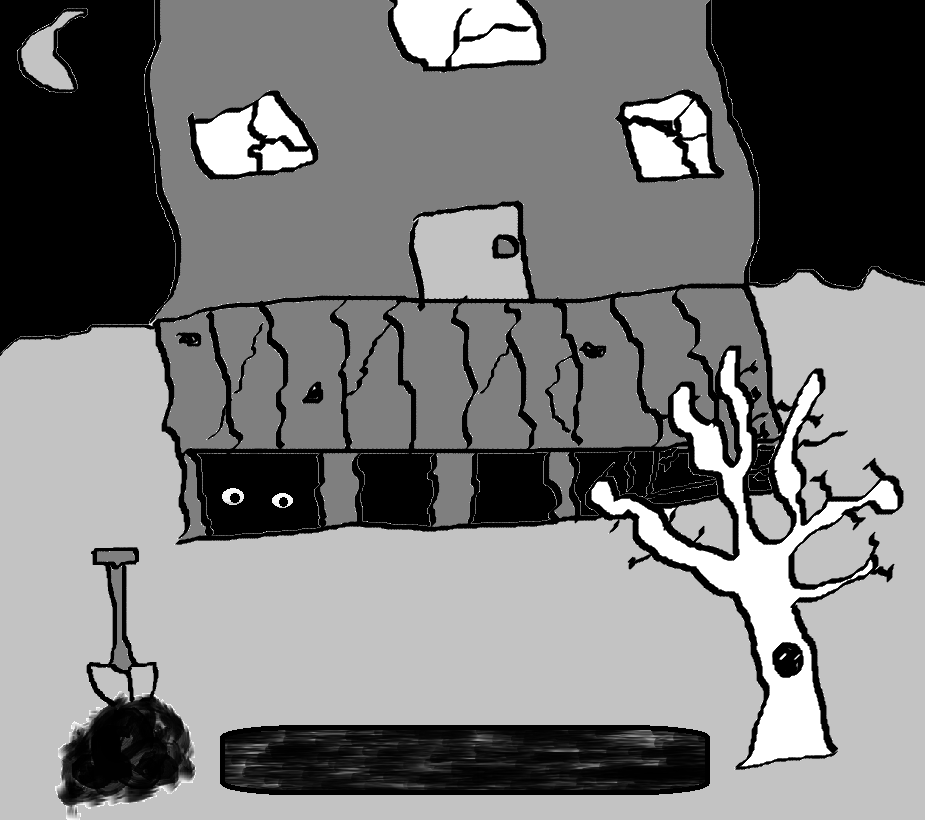

The woman hated to walk past her sister’s house. Not because it reminded her she was dead, but because from the street all she could see was the empty grave that her nephew had dug in the yard, underneath the shade of the poplars by the creek that fed itself into the lake. It wasn’t for her sister, she was already sitting in an urn somewhere in the garage. Rather, her twenty two year old nephew had dug a grave for himself in the prime of his life. “You don’t show any signs of dying in the foreseeable future,” she said, “there’s no sense in digging a grave for it to sit empty and unused for years, even decades.” The boy had replied that anything could happen, that it don’t do well to presume good health. He said that her unfettered optimism was like wearing tin shoes in a lightning storm. She didn’t know what that meant, but a knot grew in between her eyes when she thought about it and pulled tighter as she walked by the unfilled hole.

The boy went under the shade of the poplars on the hottest day of the year and introduced himself to the earth with the dull clunk of his spade. About two feet down the topsoil gave way to dull red loam, a thick clay that wrenched sweat from the boy’s brow. He dug a hole eight feet long, using himself as a measuring stick. He figured he could do the same when he reached the bottom, as he would know six feet deep when he could no longer see the ends of the patchy grass from his tiptoes. He kicked his boots into the walls of his fresh grave to establish a foothold, and pulled himself to the surface. It ain’t just a hole anymore, he thought as he pulled himself up. Now it’s special. The woman’s complaints rung somewhere in his head, and he squared the corners with a hand trowel before he raked the mountains of red clay into the brown soil until they were spread evenly throughout so any passerby wouldn’t see that there had once been a person-sized mound of red clay sitting upright in the spot. There, he thought, ashing his cigarette into the grave. She can’t have complaints about a job so pretty as this.

The woman stopped as she walked by the house and looked at the hole, only partially visible from the street. She wasn’t the type to spit, at home or in public, but she spit on the floor and put her hands on her hips. How was she supposed to sell a house with such an unsightly blemish? She had asked her nephew so much. “What might I say to a nervous buyer? People are picky enough about making a big decision like buying a house without a six foot reminder in the front they might die someday.” Might got nothing to do with it, the boy had said. That’s one thing you can presume.

The boy’s mother had never moved into the house, and instead had moved into hospice. She died of about six different things right as escrow closed. She bought the house as a fixer-upper, a place she could grow old in, replacing the wallpaper and making repairs to the foundation as her posture began to fail her. Now her sister had been left with the chore of trying to sell a house held up on one side by a growing family of cinderblocks (the former owners lifted up the porch and added about one a year) and a morbid pit in the yard that, just last week, a raccoon had started a new family in.

She had let her nephew stay in the house until it was sold, to keep burglars from stripping the place for copper. “It might be the most valuable thing about the place,” she had told her husband. She had never had children, and when her sister died she decided to take an interest in the boy as if he was her own. The boy slept on a thin cot he laid down in no place in particular, where he ashed his cigarettes directly into the carpet, and when she showed the house to potential buyers he rolled the cot into a closet and left the stain bare.

Early the next morning, the woman entered the front door of her sister’s house and spoke in a clear voice to her sleeping nephew. “Get up,” she said “we’re taking you into town for a treat.” The boy didn’t ask where they were going and they listened to the road under the tires of her old blue Honda instead of speaking. The summer sun pounded down on the black road but neither of them opened a window, despite the fact that the air conditioning had been broken for some years. The woman didn’t allow smoking in her car, and was afraid that the boy would take it upon himself to light a cigarette if she opened a window even for herself.

They arrived at Dairy Queen 20 minutes before the doors opened, and the woman sat with her hands folded over her purse on the bench in front of the store while her nephew paced and smoked. When the doors opened, she ordered a dilly bar for herself and a double banana fudge sundae for her nephew. She made efforts at small talk, but he was no more interested in conversation than he was in the sundae, which melted quickly under the hot sun as he ate the crushed pecans that sat on top. They sat for twenty minutes after the ice cream had melted. The boy drew in the three differently colored puddles with the flat end of his plastic spoon. He drew a house in what had been a scoop of chocolate, and tried to make a lawn out of the strawberry, but what appeared was a sea of flames licking at the corners of the oblong box made of sugar and milk. Eventually, it all became the same sickly pale brown, and at 10:45 the woman looked at her watch and abruptly stood and said to no one in particular “Well, that was a fine treat but we have to be leaving now.”

The woman drove past her sister’s house just as the landscaping crew was leaving. A small brown man waved to her as he reversed his truck out of the driveway. The boy’s narrow eyes widened as he looked at the front yard. Small green rose bushes had been installed in a straight line facing the street, but he never gave any sign that he noticed them. Instead, he swung open the door and leapt out as the car was still moving. “See the rose bushes, honey?” the woman called after him as he ran into the yard. “They’re for your mother. They’ll be how we can remember your mother.” The boy fell to his knees and looked at the eight foot rectangle of newly packed light brown dirt in the shade of the poplar trees.

They fought for the better part of an hour, but the boy had fallen silent after she told him she had already removed the shovel from the woodshed out back. “Honey,” she had said, “It’s just not practical to leave a big eyesore in the yard there for some indiscriminate amount of time. We have to sell this house before the bills start being due on it. I presume you have the money to pay those bills? Because I certainly do not.” The boy remained silent as she lectured him except for one phrase he repeated in a low voice, sounding out the words clinically like he was reading a definition of some scientific term from a dictionary. It is my birthright, he said.

The woman lay awake in bed that night feeling satisfied. She felt she had talked some sense into that boy. I bet this is how King Solomon felt, she thought to herself over the sound of her husband’s soft snoring, when he cut that baby in twain. “This ain’t any kind of goddamn birthright,” she had told the boy, slipping back into the tones of her childhood she had tried so hard to forget, “I mean she just bought the damn house. There ain’t nothing promised to you, least of all an eternal resting place in someone else’s front yard.” He’ll have to come to reason now, she thought and smiled, settling into the sheets and looking out the window at what she would come to recognize as wisps of smoke just beginning to emerge from beneath the porch across the street. Later, a broad-shouldered firefighter would tell her that a cigarette had been laid in a pile of dried brush, her nephew watching until the end from that dark, lonely place underneath the house.