Transformed

Transformed

He had turned into a cat sometime in the night. He woke up inside the little cornice up at the top of the concrete embankment right underneath the interstate. His sharp cat ears caught the high whine of the cars overhead and the rumbling echoes of the slower cars passing underneath and it all mixed into a solid wall of cacophony like the wail of the damned. How long he’d slept through that he had no idea. He smelled the strange odors of the blankets around him, hissed, stopped and smelled them again and realized they were from his own body, or the body of the person he’d used to be.

He took a drink from a rainwater-filled pothole next to the storm sewer and he had the idea that he might check his reflection to see what kind of cat he had turned into. He had always liked cats and knew a lot of breeds and patterns. Tortie, tabby, snowshoe, Siamese, Russian Blue, Scottish curl. He lapped greedily around the bright oil stain atop the puddle. He looked at the face of the cat in the puddle but it didn’t look like anything to him. As a cat, the self-awareness necessary to recognize himself in a puddle didn’t come naturally. He looked and looked at that puddle, trying to bring together his own selfhood with the picture of that cat, but the closer he brought the two ideas together the harder they pushed apart, like two magnets with the same charge.

Later on he would be pricked by instinct to clean himself, and discover that he could bend his spine far and see quite a bit of his own body, but he only dimly remembered the puddle incident by then and his body didn’t look like much to him.

Being a cat was a series of urges, panics, and jolting immediacy. He awakened hungry and would be hungry and stayed that way, the need sitting sentry at the bottom of his stomach like a watchful stalking shadow in the corner of a room. All the time too he needed to rest, and every time he caught a sunbeam a wave of tiredness dampened his mind, and he had to fight the urge to nap, and often lost. His ears, his whiskers, his nose, the nerve clusters along his face and at the base of his tail, all constantly tingled, needling his mind, pulling his focus this way and that. His visual field was muted and he couldn’t get used to the way his eyes focused. He was a tangle of wrestling phantoms each jostling its way to the front, shouting and demanding attention. Whenever he tried to make a plan for further ahead than the next few minutes it would soften and crumble under the strain of all this chatter. The way he was grappling with higher brain functions caused a low-level panic that it took all his mettle to suppress.

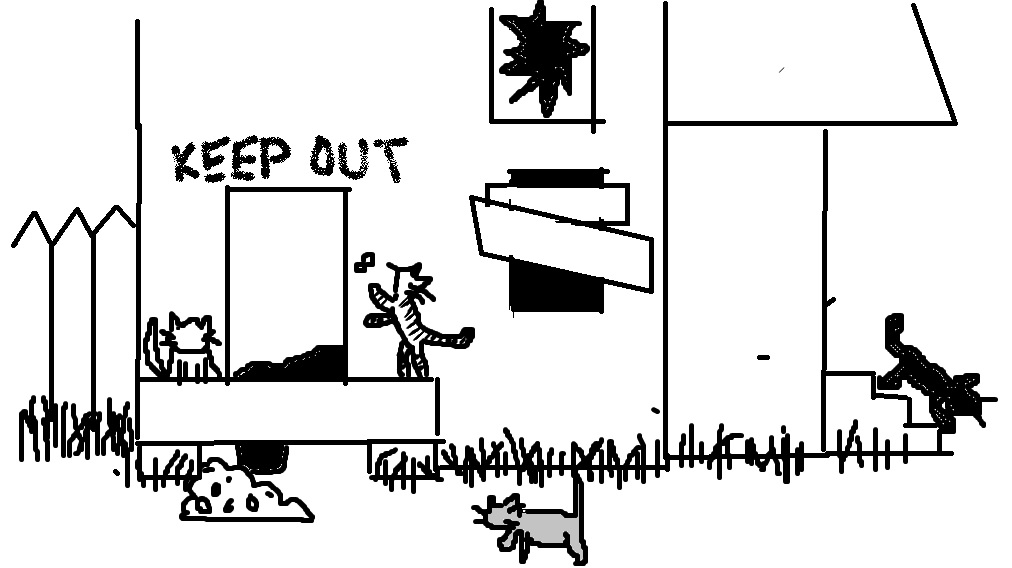

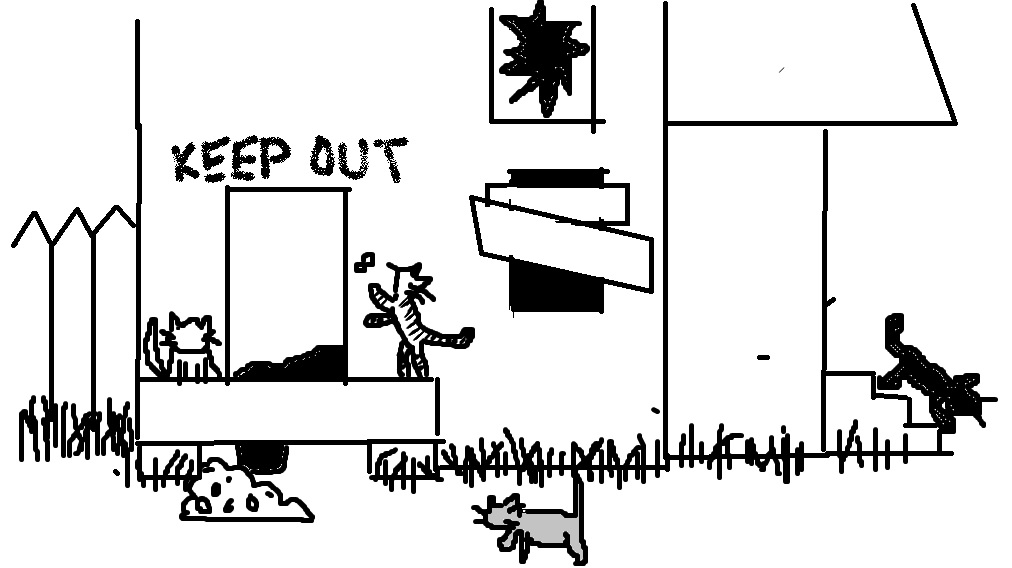

He made his way to the derelict house on the end of the block he lived on once. A revolving gang of at least a dozen cats lived in the dank basement that could be accessed from the outside via the rotten porch partially covered up with particle board and the rabbit holes that the cats had dug in the places where the foundation was falling away. He’d never been inside there, only passed by the house on his way to somewhere or other. The elderly retired neighbors fed them, he knew, and watered them, and when there was a snap of cold weather coming in stacked boxes wrapped in some sort of crinkly heat-trapping substance for the cats to sleep in. These neighbors always used to chase him away, but being a cat now he could walk right in.

The house was in worse condition inside than he had ever dared to guess. The entire ceiling in the living room had fallen in. It must’ve happened sometime after the cats had already claimed the house because there were several leathery cat corpses beneath the rubble, which the cats had nibbled a little left to mummify beneath the choking dust. He took a look up the wobbly stairs and found a bedroom with a large blood stain on the far wall. He’d heard what had happened here was some guys were cranked up and fucking around with guns and there was an accident. Some cat sense within him was able to smell the blood, detect some mixture of chemicals that met his nose as heat and fear, that didn’t mix well with that story, but it hardly mattered.

The other cats jumped in and out of the light and looked at him with bemusement. They weren’t really interested in him so long as he stayed on the other side of the room from them. Some hissed at his smell. He was amazed that they could tell his smell apart from the dander and oil and piss and shit smells smeared everywhere which combined in his nostrils into a brown soup.

He heard footsteps on the back porch and saw the retired neighbor pour food into huge tin dishes and murmur nicknames to the swarming cat horde. He ran to the porch and quickly discovered that there was a pecking order that determined who got the food and in what order. The established cats of the house, the cats whose fresh smells the other cats could detect mingling with the dust in the broken-up hallways, went first. Each cat had underlings allowed to feed alongside it, but it wasn’t a concretely-set system because some cats wouldn’t feed in the presence of certain other cats and some cats wouldn’t be allowed to eat anything in the presence of certain other cats. There were also cats who weren’t permanent residents, who just dropped in, and some of these cats were underlings of other cats and others formed a little cast-off clique that fought for food amongst itself. And of course, you had to account for other absences, a cat who was usually there but wasn’t there now because it was exploring or rutting or fighting or lying run-over in an alley never to return. Keeping all this straight was like trying to make a train schedule in your head.

He found three cats he could count on to let him eat, simply through trial and error: one fluffy white and brown with mats in its fur the size of ping pong balls, one monstrous orange tabby with a wide face, so big he barely needed to lift a paw, and one skinny little Siamese who kept the other cats on their toes by absolutely psychotic random freakouts. But often they were missing, and that meant he often didn’t get any food, and when this happened he was off on his own to pick through a dumpster or to beg at people’s back steps for dinner leftovers. He thought he could hunt his way out of hunger, but he was too domesticated. His pounces were lazy, untrained.

Living in the house was a dicey proposition even when it wasn’t mealtime. It was poor shelter in pretty much any weather. In the daytime the air grew stuffy and oppressive within the dusty, shuttered windows. At night drafts came in from all sides and chilled to the bone, and if he’d found finding a spot at the food dish hard then finding a cat pile to lie on, even for the simple expedient of conserving body heat, was downright impossible. When he tried to sleep alone the constant cat traffic kept him up. He would be minding his own business in the corner of a room and a cat would come up just to swat at and fuck with him. The only place he could count on a bit of rest was the small fenced-in backyard, the cleanest part of the property by far.

He used this bit of open space to put his body through its paces, just to feel it out. There was much he could do but much more he bafflingly couldn’t. He tried to wiggle his tail and found it harder than expected. It could move just fine, but it wouldn’t obey him when he tried to make it, say, stick straight up – he knew that was a sign of contentment, and he wasn’t content. His claws likewise wouldn’t come out on command and only came out when he was full of bloodlust – chasing a bird, fearfully swatting a hostile cat who tried to muscle in on his patch of daylight while he slept. He wasn’t as good at jumping or climbing trees as he expected to be, so he mainly just stuck to the ground. He knew, from some sliver of human intellect still buried somewhere in the rag heap of his brain, that the world ought to look much larger to him, being of a small size, but when he looked up at houses, across streets, at cars in the distance, everything looked just as big as before. Whether this was a function of his new eyes or his new brain he didn’t know. Only the presence of humans made him feel small.

He knew he should ingratiate himself to people. They would feed him, maybe they would take him home and give him a warm place to sleep. He was cute now, loveable, pettable, or could be. But he found his treatment at the hands of humans just as spotty as he had. Some stroked him in a rushed way and hurried off. Some kicked him. Small children yelled at him and pulled his tail. These experiences left their mark, and he couldn’t make himself sidle up to humans the way he’d seen street cats sidle up to him all his life. He’d always assumed it was an act, self-interested, but it wasn’t – or maybe those words didn’t mean the same for people as for cats, because he found himself unable to pretend he wasn’t afraid. There was some layer to human consciousness that when removed made dissembling impossible. No matter how he told himself it would be better if he stowed his fear, he couldn’t do it, and no one he ran into had the patience to work him through it.

One day he detected a new smell coming off of him. Suddenly the refuge of the backyard was broken by whale eyed cats that circled like sharks. He realized he was a queen, and he was in heat. Of all the indignities. Powerful chemicals were barreling through his bloodstream. Manic obsessions filled him, and unprepared he gave himself fully over to them, licking himself all over trying to quiet the crawling feelings in his skin, smelling all over, the butt, the scent glands, the swollen genitalia he was horrified to recognize as his. He smelled the sprays of toms and they lit up his nose like flames. They saw him take note of their sprays and followed him. He tried to get away, hide up trees, in the narrow gaps underneath dumpsters, and they tracked him and made unnatural guttural noises. They bumped into each other. Screamed. Hacked at one another. Fur and skin flew. He smelled blood and cowered.

This kind of fear wasn’t new to him. On the street, in the camps in the woods, things happened now and again. But never did he suspect that his own body would betray him and give him up to the enemy. Instinct throttled him in a grip of wire, and when a huge snaggle-toothed tom muscled his way to the front he felt his legs raise, raise to the victor, leaving that fragrant wet lump open and exposed and he felt the tom bite his neck, felt the teeth pierce and move around beneath the floppy skin there, and the cat’s barbed penis pummeled him cruelly like someone had stuck a drill in there. Once the act was complete those zombie urges retreated and he swatted at the hateful attacker, aiming for eyes, throat, hoping to injure it, hoping to leave it unable to menace another queen ever again, and dwelling in immiseration, at least until the carnage began anew and the zombie in his blood rose again.

After getting pregnant he avoided the cat house. He knew he wouldn’t get a moment’s peace there. He wandered up and down the cracked alleys, keeping his expanding flanks flush to the fence to avoid the bouncing pickup trucks. He stopped by the dumpster of the Mexican bakery and though it tasted like Styrofoam to him he ate the edges off several stale loaves. Hunger still gnawed at him. He licked the wrapper from somebody’s Subway. He caught a smell wafting in from somewhere. It stirred something in him. He wandered in the direction of the smell down an alley, up a gravel driveway.

It was her. It was really her. God how long had it been? How long ago had she thrown him out? Months, years melted into candle wax inside this cat’s brain of his. She was making chicken wings. She had a special fry batter recipe, corn meal and milk and egg and cayenne pepper and garlic and just a pinch of finger-crushed cumin seeds, he didn’t know what all was in it but he’d know the smell anywhere, couldn’t miss it with this cat nose of his. He began daydreaming. To get just one of those wings. To sink his sharp tooth into a wing and gobble the skin right down. She’d made him those wings, and then she stopped, and now she was bringing out a plate piled high with these wings out to the garage that he had once cleared the cobwebs, banged up with a hammer, poured new concrete to fix the crumbled cracks and pits. He had no idea why he’d given all that up, literally couldn’t remember.

The garage had a picnic table in it. His old woman was bringing out the plate of chicken wings to a group of men sitting around it. His brain was too far gone into cat world to make out what she was saying to them. He didn’t care either. The growing kittens inside him screamed out for nourishment. The scent memory of the chicken wings acted on him like a tonic. He had room for nothing else in his mind. The smell had him feeling more calm and content than he had in weeks. While the men laughed and bullshitted around the table he leaped up as sneakily as he could. He nibbled on the bony knob at the end of a wing.

One of the men shouted to see him on the table. He pushed him off. Undaunted, he jumped back up again. He mistimed the jump due to his changing body and ended up clinging to the edge of the table, claws sunk into the vinyl table cover. Drinks on the table rattled and a couple spilled. The man who had shouted before shouted louder, picked him up by the tail and dashed him against the concrete floor he’d helped pour. Everyone else around the table laughed and babbled drunkenly. The man muttered something and walked to the end of the driveway, still carrying him by the tail, finally throwing him down storm sewer.

It was dark and wet. His skull was cracked. Blood poured into his eyes. He could only with difficulty hold his head out of the dirty leaf-strewn water. Blackness crept in at the edges of his vision, and he took comfort in the fact, or rather in the hope, that when the darkness closed all the way in he would reawaken in his old body, in his old blankets, on that ledge beneath the underpass, with human ears taking in the muted and manageable noise of the traffic.